Navin says, “scRNAseq is the workhorse in many projects, but it’s just the starting point. It tells you what’s there and what different cell markers are. Pretty quickly afterward, you want to know which cells are next to each other, who’s interacting?”

To that end, the collaborators employed various spatial platforms. While they are a newer technology, they enabled the team to see how cells are organized in tissue, account for inconsistencies between RNA and protein levels, and validate selection biases from cell survival after dissociation.

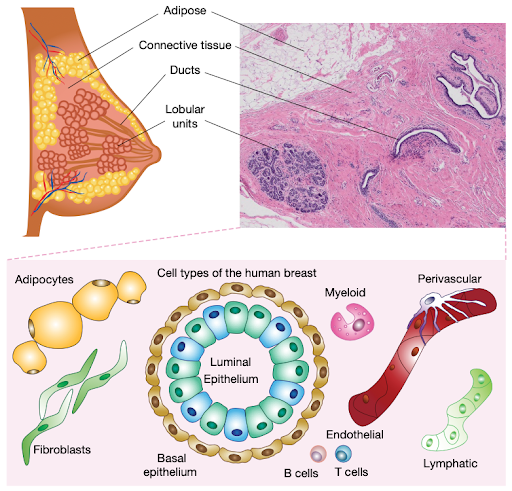

For example, the HBCA found variations in cell states depending on age, self-reported ethnicity and menopause. Presumably, future studies sampling from lactating or developing individuals and further ancestries would uncover additional cell types and states, reflecting the true complexity of human tissues.

Seven years in the making

Funded by CZI as part of the Seed Networks for the Human Cell Atlas, the HBCA project took seven years to collect and publish its findings and is a project with many more years of discoveries ahead.

Challenges in producing a high-quality atlas

“People ask why it took seven years,” Navin says. “But a lot of it was the validation and the spatial analysis that we thought was really important.”

According to Navin, the biggest challenge in the project’s early days was standardizing protocols between the two groups at MD Anderson and UC Irvine. They realized the impact this could have on their data and wanted to ensure they consistently integrated the results while minimizing the loss of biological signals.

“We got early data back that said which critical parameters have the biggest influence on skewing the cell types and representing them. And for us, it was the dissociation time: the amount of time that the cells were in the enzymatic buffer,” Navin explains.

For example, they found that leaving tissue in the dissociation buffer for longer enriched some cells, like myoepithelial cells, and led to fewer immune and vascular cells. By systematically testing different incubation periods, they found that three to six hours was the sweet spot for all the cell types they hoped to capture.