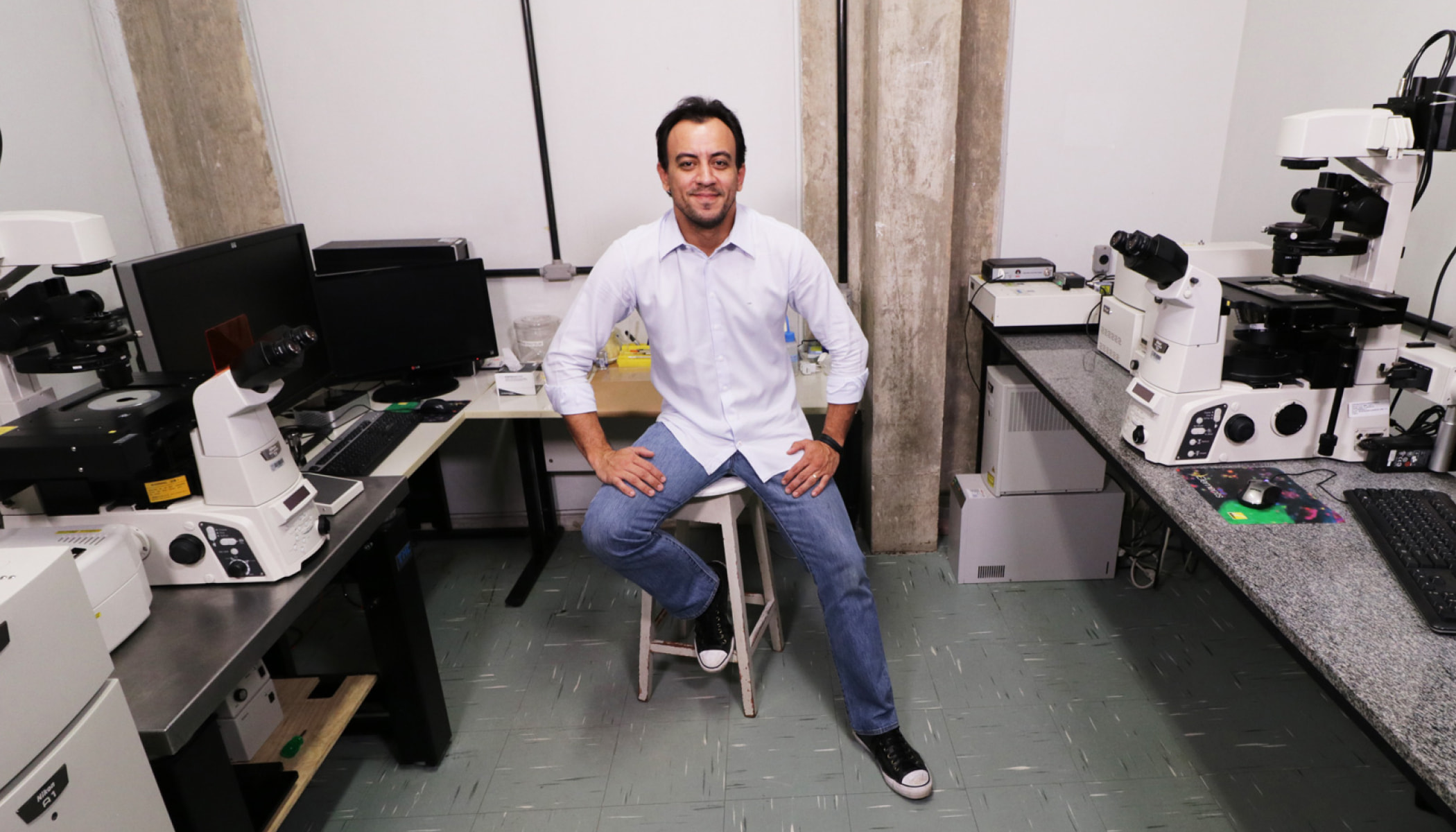

Imagine playing chess without knowing all the rules. The analogy, adapted from renowned physicist Richard Feynman’s explanation of attempting to understand natural phenomena, was more or less what biologist Gustavo B. Menezes, of Brazil, experienced before he was exposed to a new world in imaging.

“I remember it just like yesterday,” Menezes says of the moment he was introduced to bioimaging. “It was love at first sight.”

The most routine lab microscopes work well to examine isolated samples of tissue extracted from a living subject. Those were the ones available to Menezes and his colleagues in Brazil at the time.

More advanced microscopes, in contrast, allow researchers to examine biological processes within a living specimen — or, in vivo — in real time and all at once. Whole organs or even an entire living specimen can be imaged while it conducts its normal biological functions, giving researchers the ability to witness interactions at various levels of cell structures.

“[Knowing] how cells connect, how cells kill bacteria, how a molecule travels from one place to another,” Menezes explains of its application, “this has opened huge doors in our knowledge about biology.”

Access to what Menezes called “a whole new world” in biology, however, was limited in Brazil due to the prohibitively high cost of bioimaging microscopes — but he was determined to change that.

Thanks to a chance encounter with a technician who taught him everything he needed to know about the equipment’s specifications, Menezes spent the next several years redesigning bioimaging equipment, ultimately bringing the cost of a microscope capable of in vivo imaging down to a fraction of what it was.

Menezes then shared the redesign with the rest of his country with the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative’s support, emphasizing access to more remote labs and scientists of all skill levels.

Today, Menezes and his team are able to visit labs in all 26 states of Brazil to advise and support other researchers in building or acquiring their own bioimaging microscopes based on his redesign, which has since led to the publications of more than 120 research papers by scientists who otherwise would not have access to the tools necessary to conduct their research.

Early years in bioimaging

Menezes has spent his life dedicated to the sciences, completing a master’s degree in biological sciences and doctorate degree in physiology and pharmacology. But it wasn’t until the end of his doctorate that he first encountered bioimaging. He was presenting his thesis defense when a professor in the committee suggested he use in vivo imaging in his research.