In a recent trip to California, biomedical scientist John Tembo brought along some unusual cargo: tubes of bodily fluids collected in his native country, Zambia. Back home, John had been tasked with investigating undiagnosed infections in this African nation of 18 million people. While technologies exist to do this, most are not accessible to those in low- or middle-income countries, where the disease burden is the highest. John was traveling to San Francisco, tubes and all, to learn more about an open-source, cloud-based analysis platform called Chan Zuckerberg ID (CZ ID) and its potential for improving public health.

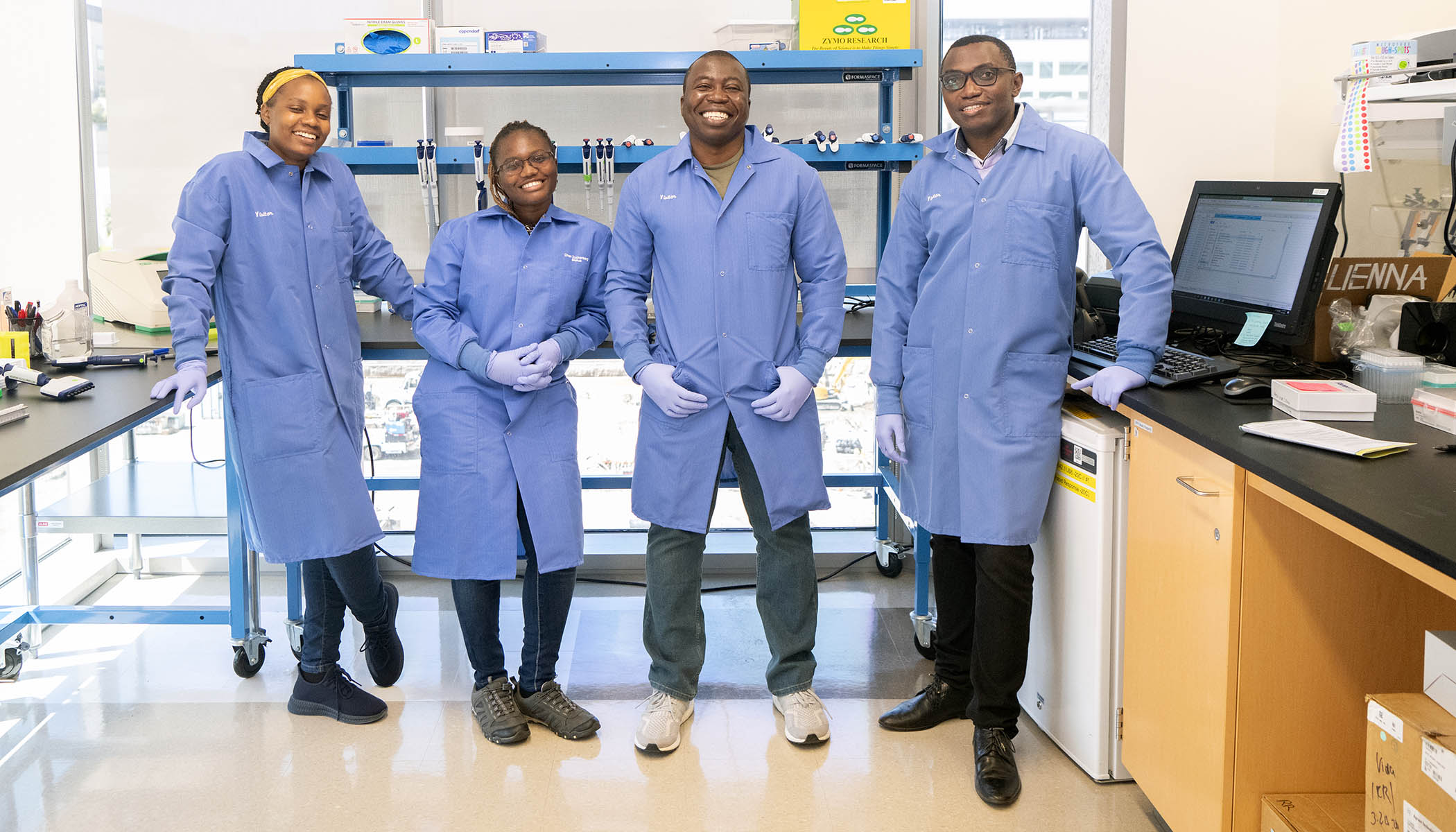

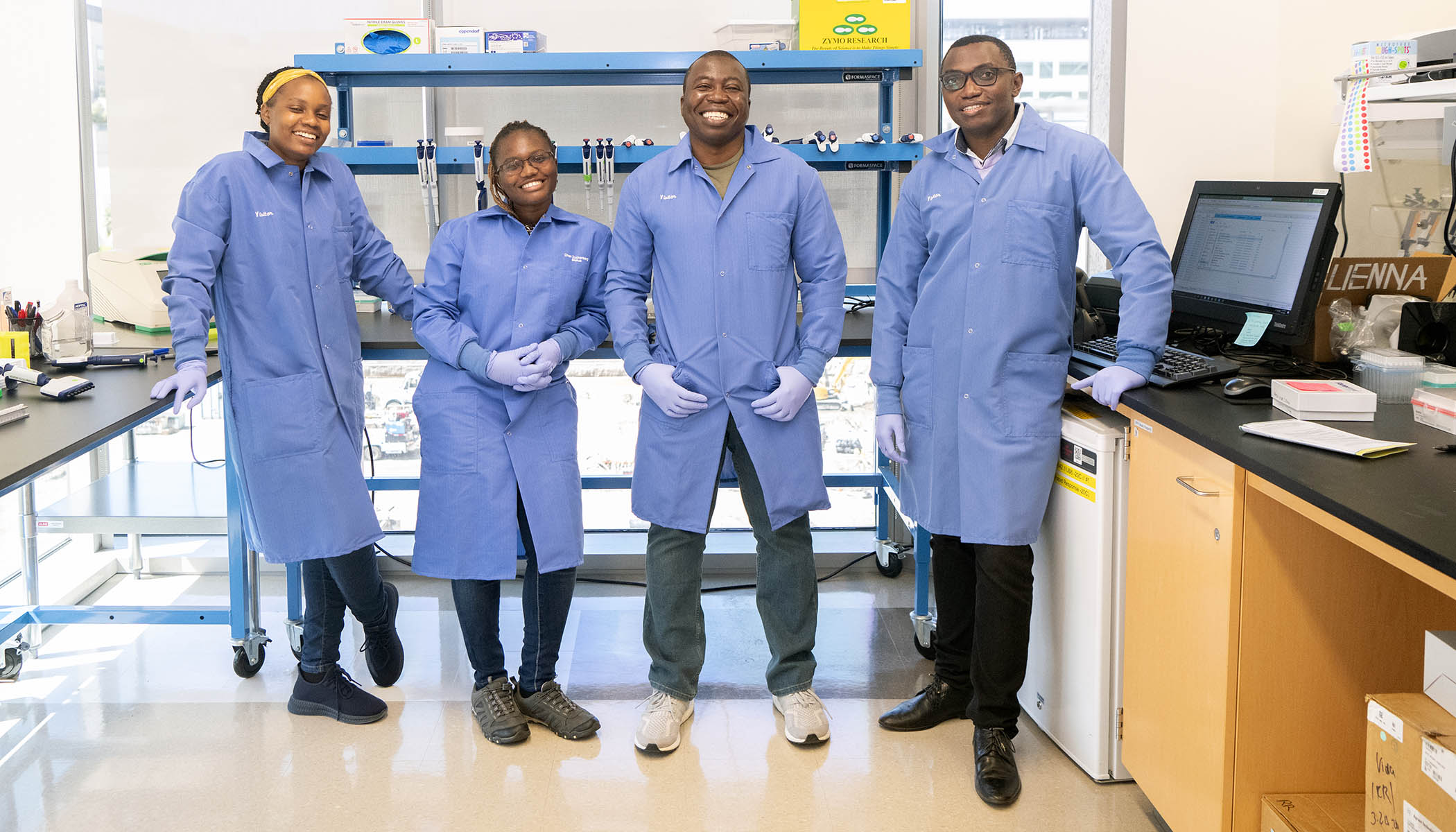

While in San Francisco, John and his team trained on the ins and outs of this tool and on how to perform the next-generation RNA and DNA sequencing that generates the data CZ ID analyzes. They worked closely with scientists at the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub (CZ Biohub) — the nonprofit research institution responsible for co-developing CZ ID with the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative’s (CZI) product team.

Back in Zambia, the researchers are applying what they learned in their own labs, while still in daily contact with their partners at the CZ Biohub and CZI. They have become part of a global network of investigators detecting and tracking disease with CZ ID, all thanks to a project that began in an academic lab.

The team of researchers from Zambia is still in daily contact with their partners at the Biohub and CZI. (Photo by Barbara Ries)

The birth of CZ ID: Spotting pathogens in real-time to prevent disease outbreaks around the world

Two decades ago, University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) molecular biologist Joe DeRisi created a new technology to help detect the cause of illnesses: a piece of glass coated in bits of DNA that trapped and identified viruses with matching genetic material.

This device, ViroChip, could ultimately be used to look for every known virus. It could detect the rhinoviruses that cause the common cold. It also found the SARS-1 virus early in the 2003 outbreak.

“No one was doing this when we started in 2003,” Joe says. “People thought of this as a fishing expedition, a high-risk project with little chance of success.”